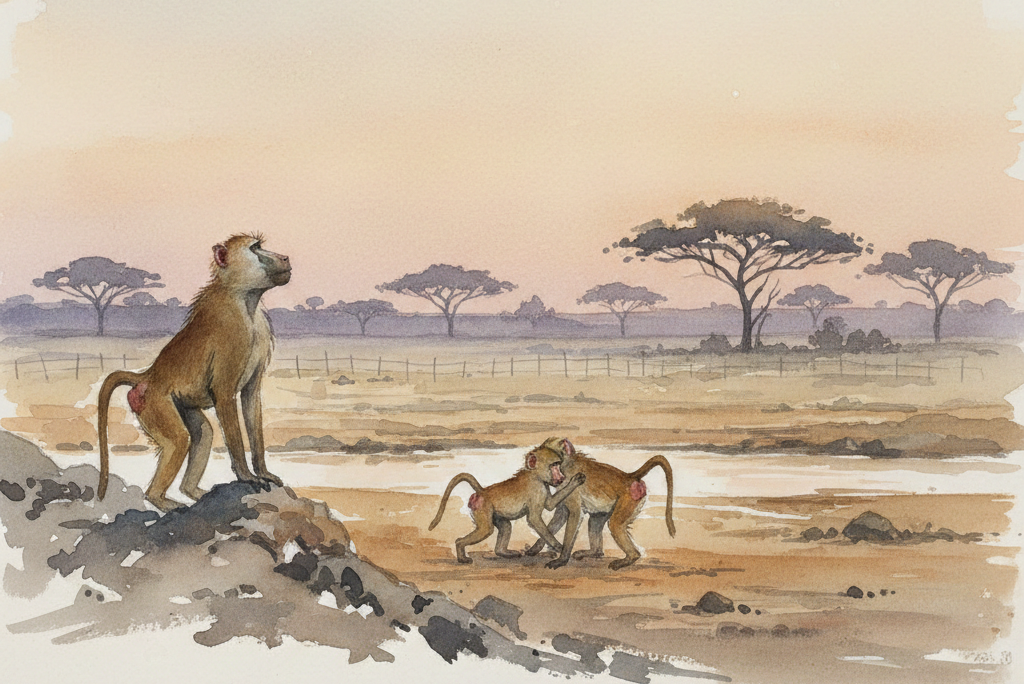

Baboons are clearly intelligent. There's something distinctly human to them. Watching them on safari in the Kruger National Park, it almost seems impossible they don't just get it: that they're in a fishbowl, fenced in, and being watched by humans.

They certainly seem to approach the raw intelligence required. The evidence is right in front of their eyes. It feels eminently obvious to us.

But what they lack is explanatory knowledge. How can they understand the concept of a national park, something even humans had only thought of in the last 200 years? For that matter, how can they even understand its constituent parts? Even if a baboon has encountered the perimeter fence surrounding the park, why should they know a human built it? After all, most baboons would not have seen that construction themselves.

Same goes for the park roads we drive on. Why should they think those are any different than the abundant animal paths everywhere? They don't understand what a car is, or the internal combustion engine, or a wheel, or glass, metal, language, conservation or a nation state. They are like a human baby before they absorb the collective knowledge of thousands of years of human culture into their brain.

Our ancestors understood none of those things either. That seems silly now. But yet we're not much more intelligent than they were, biology doesn't change that fast. We're just standing on centuries of good explanations that they did not have access to: we're seeing the world through generations of theories that we take for granted - ubiquitous background knowledge.

The baboons can't just look at the evidence around them and immediately understand what it means any more than our ancestors had any hope to look at the stars and understand they weren't just a sparkly dome roof over their flat earth.

With the baboons' high intelligence, they seem to come up with some rules-of-thumb after careful observation: it's good to stay out of the way of the big noisy moving boxes, sometimes they carry oranges that you can steal, etc. But understanding what a national park is, is an altogether different kind of knowledge than knowing the truck tends to carry sweet oranges: it requires you to connect all these different observations into a universal theory that explains the "why" behind it all.

A theory that has reach. Once you understand the concept of a national park, and agriculture, then it won't surprise you if the safari truck switches to carrying bananas, even if you've never seen it happen before. But if you don't understand what a national park is, then this is a surprising development - just as surprising as if they started carrying baseball bats, Canadian flags, or live chickens. Without explanatory knowledge, the world seen through baboon eyes is a random and incomprehensible place.

Gaining explanatory knowledge is not easy.

To understand the concept of a national park, a baboon would first need the curiosity to ask "why?".

Then it would need the creativity to guess a theory that explains each of the parts of the Kruger that we take for granted. Then it would need language to spread that idea to their troop. They would need to convince their troop to accept their theory if it has any hope of surviving. Even if they had language (and writing), the troop would benefit from a culture of free speech - otherwise they might kick the baboon out for being out of line or offensive. After all, even most good groundbreaking ideas were controversial when they were still fresh and strange.

Still, this theory would likely be wrong. After all, making exactly the right guess the first time would be unlikely. And even if it's right, it would inevitably come up against many competing theories from other baboons that are straight up wrong. What if the elephants made the roads? Or the evil baboon troop that lives across the park? What if the park fence was simply the edge of the world put there by a primeval half ostrich - half lion?

To pick the most accurate one, its best to have a culture of criticism and scientific testing. This is something humans only really solidified during the Enlightenment and that the physicist-philosopher David Deutsch believes turned us into "universal explainers". He calls this "the beginning of infinity", since it opened the door to unbounded open-ended explanatory knowledge creation.

They would need to continually improve upon their ideas with discipline by eliminating the errors in their understanding. And over generations, they might have hope to put together a comprehensive explanation of what the Kruger National Park really is - the nature of their universe.

To rise to this level is hard. It took humans nearly our entire history. If you're a baboon, it's much more fun to just hang out in a tree, eat fruit, and ignore the human cars passing by.

And so, humans remain the only part of God's creation with a genuine ability to create new explanatory knowledge.

I think this doesn't only apply to seeing truth, but also beauty.

Driving around Kruger National Park, I recognize that I can experience beauty that an ant can not. The individual ant can barely see, even less comprehend the beauty of their colony's giant anthill. The antelope could perhaps process this, but in trying to outrun a lightbeam out of misunderstanding that it is a predator, it betrays that it could not possibly comprehend the beautiful colors and contrasts of a sunset. Elephants mourn their dead, so might be able to grasp the beauty of life, but without language could not grasp the beauty of an inter-generational narrative.

It seems then that, as intelligence increases, so does our capacity for recognizing beauty. But, again, I don't think that's all there is to it.

The antelope misunderstands the lightbeam because it lacks explanatory knowledge of what a spotlight and safari vehicle is. It feels obvious to us, but that's because we've invented those things.

Perhaps the true limiting factor to seeing beauty around you is simply knowledge, and it's just that intelligence is upstream of that: you need some level of intelligence in order to have the capacity for producing knowledge. Once you have knowledge, the world becomes alive with ideas.

To our eyes, stars still appear as specks of light. Yet, due to modern knowledge, we look up and marvel at billions of distant fusion reactors of dizzying size hanging in the sky. We don't see more stars than the caveman did, but we see more in the stars.

And I wonder, what great beauty is there in this world that goes missing in plain sight, because we don't understand it yet?